Interview with author Huang Beijia

Posted on December 14, 2021 by helenwanglondon

Huang Beijia 黄蓓佳 is a much-loved writer of children’s books. Her first novel for children, the modern classic, I Want To Be Good (《我要做好孩子》is the story of ten-year-old Ling in her last year at primary school, navigating the stress of the adults around her. It’s about the pressures of growing up, and about being happy being yourself. This funny, feel-good book has just been published in English, translated by Nicky Harman. We interviewed Nicky about translating this middle-grade novel last year (no. 97), and we’re delighted that Huang Beijia agreed to an interview with us too!

Please tell us about yourself. What would you like our readers to know about you?

I was born in the 1950s in a small town in the lower reaches of the Yangtse River. My parents were both middle school teachers. Reading in childhood and adolescence was the most wonderful experience of my life. I spent four of my teenage years as a farmer on a small island in the Chang jiang (Yangtse River). Life was very hard then, and I started to teach myself to write fiction under a kerosene lamp. In 1977 I passed the university entrance exams and was accepted as a student in the Chinese literature department at Peking University, the best university in China. Chinese universities had been closed during the Cultural Revolution, and when the entrance exams started again in 1977, the competition was intense. As a result, I found myself among the most talented people in China. I studied literature, aesthetics, philosophy, literary theory and foreign literature, and at the same time started creative writing in earnest. I’ve been writing for fifty years now, and must have published more than 5 million characters! When I was younger, my writing focused on the life of intellectuals. After I turned forty, my daughter’s experience of growing up triggered my interest in children’s novels. Gradually I found myself writing fewer works for adults and eventually spent all my time and put all my heart into writing for children, which I love. I have many readers in China, and it’s such a pleasure when people come up to me in the street and say: “I grew up reading your books, and now my children are reading them!”

We’re delighted that I Want To Be Good has been published in English in the UK. Could you tell us about this story, what inspired it, and the circumstances in which you wrote it?

China has a large population and the competition in education is fierce. From the day children start school they are involuntarily caught up in a learning competition. Every week of every month of every term they are oppressed by the nightmare of one exam after another, until they are accepted by a top-ranking university, thereby fulfilling their parents’ ideal. In 1996, when my daughter was about to finish primary school and move up to middle school, she and I went through a whole academic year of “examination wars”. I felt scarred by the experience, and had many thoughts and emotions about the education system in China. I Want to Be Good was based on my daughter’s story. Because I was already familiar with the characters and scenes, the writing came easily, and I finished the book in about twenty days. It was published 25 years ago, and has been a favourite of children, parents and teachers across China, selling more than 5 million copies and earning many prizes. It has been adapted into a movie, a TV series, and for the stage. It’s also loved by children outside of China, and has been translated into English, French, German, Russian, Korean, Vietnamese and Arabic.

In I Want To Be Good, Ling has to navigate the pressures of growing up, while wanting to be herself. In your earlier fiction writing for adult readers, you wrote about the pressures women faced in their relationships and careers. When/how did you shift from writing for/about adults to writing for/about children.

When I first started learning to write, I wrote a few short stories for children. They are still in print, in various textbooks. When I went to Peking University, I studied literature, and after systematically studying a lot of Chinese and foreign masterpieces, I discovered that children’s literature was not the right genre for expressing my sadness and love for the world. My interests shifted towards writing for adult readers. I published more than twenty novels, collections of short stories, essays and more than 100 episodes for TV. Writing TV scripts was excellent practice for storytelling, and is the reason why my later children’s books are able to attract children to reading. When I wrote I Want to Be Good in 1996, and saw how enthusiastic Chinese children were about it, I realised that children need reading material that speaks to them. As a mother, I also felt a responsibility not only to write more works that they would like, but to write specially for children. So I reduced the number of works I wrote for adults, and increased the number I wrote for children. These days, I no longer write for adult readers, and only write for children.

Translating personal names is difficult. Is there a particular significance to Jin Ling’s name?

It’s not just translating names that’s difficult, choosing names for characters is difficult too! Names have to sound right, fit the character, be recognizable and memorable from the start. Before I begin writing a new novel, I put myself through the mill giving every character in the book a name.

I chose the name Jin Ling 金铃 because I was writing about a girl growing up in Nanjing. Nanjing used to be called Jinling 金陵, which sounds the same but is written differently. Jin Ling is an ordinary and popular kind of name, without any pretensions, and has a nice ring to it. For Chinese readers, the name feels familiar, as though it might be someone they know in real life.

Jin Ling also sounds similar to jingling 精灵, a fairy or spirit, which in Chinese has very positive associations. When I chose the name Jin Ling, a quirky little girl flashed in my mind, which was exactly how I had envisioned her.

Is there a sequel to I Want To Be Good? It was first published in 1996, so the children who first read it would be about 35 now. How has this book influenced them?

So many children wish there was a sequel, and some love Jin Ling so much that they have written their own sequels! But I don’t want to write one. Generally speaking, sequels aren’t as good as the original book, because all the best things have gone into the first book. The earliest readers of I Want To Be Good are now parents with children of their own. They became loyal readers of my subsequent books, and once their children can read I Want To Be Good, they buy my other books for them too, and enjoy reliving their childhood with them. Readers often ask me to sign books for them, and tell me that they grew up reading my books and are now buying them for their children, which is the most wonderful thing for an author.

The protagonist in I Want To Be Good is an adorable little girl, but that doesn’t prevent boys loving this book too. I met one boy who said he’d read the book at least 25 times, and knew it backwards. He could remember every scene and recite every dialogue! And in Beijing’s literary circles, there is an older literary critic who said he was reading I Want To Be Good on his own in study, and laughing so much that his wife peered round the door to check he was all right!

Please tell us about your own childhood reading. What did you enjoy reading as a child? Do you have any particular associations with your childhood reading – perhaps a special person or a special place?

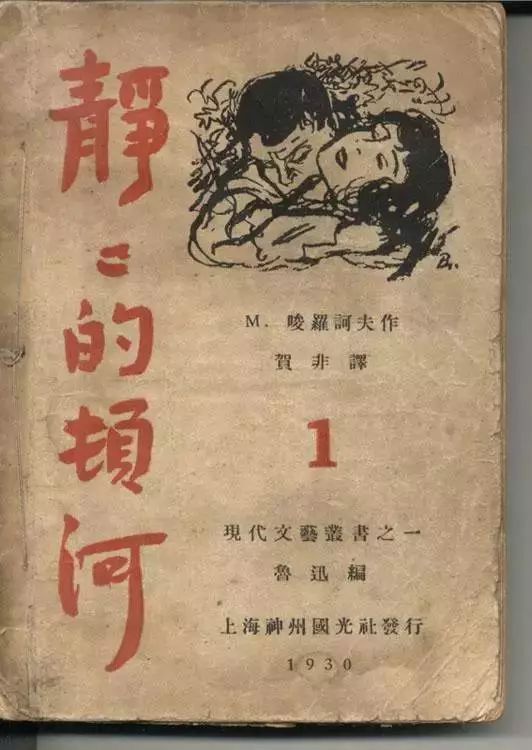

When I was a child, there wasn’t enough reading material, and because of the limited conditions, on the rare occasions when another child got a book, the rest of us would pester them and follow them around, and the book would be passed around, with each of us having only a very short time to read it. We gobbled down books. I was so desperate to read, that when there were no books available, I would find the writing on the wrapping paper in shops fascinating and intoxicating. This mad desire to read has always been an important part of my life. One of my mother’s colleagues was the head of the local middle school library, and had a wooden box of foreign novels at home. His son was in my class at school, and thanks to those connections, I read every book in that box. The ones that made the biggest impression on me were Sholokov’s And Quiet Flows the Don, novels and plays by Tolstoy and Chekhov, novels by Balzac and Hugo, and works by Dickens and a group of early twentieth-century American writers. At the time, I devoured those books without fully understanding them (in Chinese we say we “ate the dates whole”). Although I only vaguely understood the historical background and social ethics, the words had a magical power. When I was a young child, books were a window on the world, and gave me big dreams, and the desire to change my ordinary life.

Further reading

Exactly two years ago, Huang Beijia was “Author of the Month” at the Leeds Centre for New Chinese Writing, where you can read – in Chinese and English – her short story 《心声》in Chinese, translated as ‘From the Heart’ by Helen Wang.